Words: Nik, Pics: Simon Everett

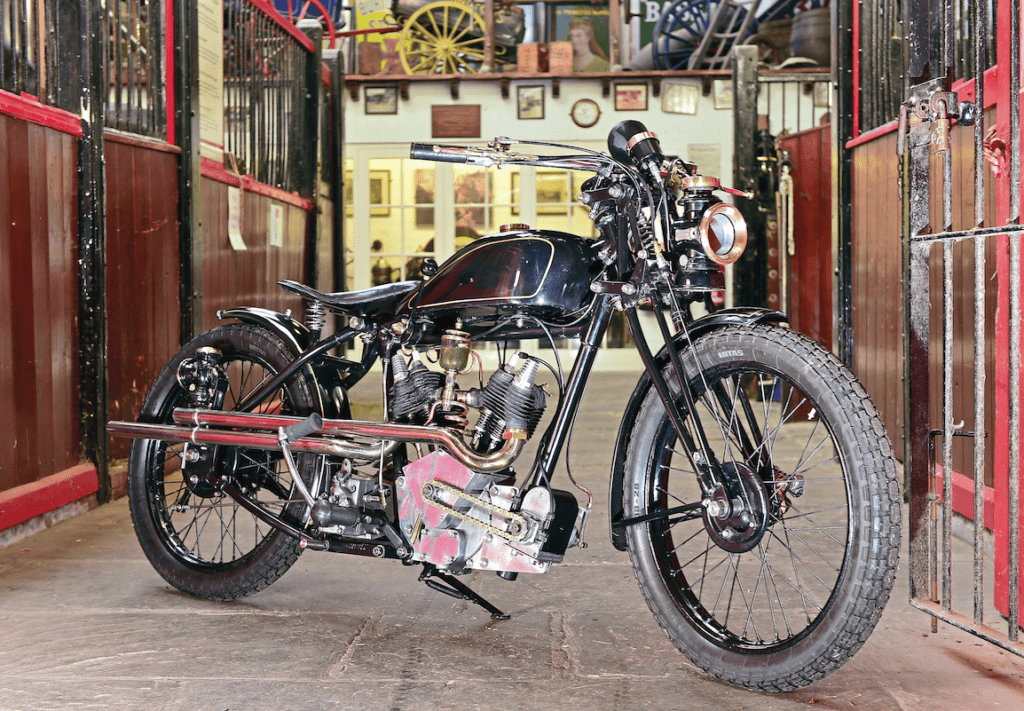

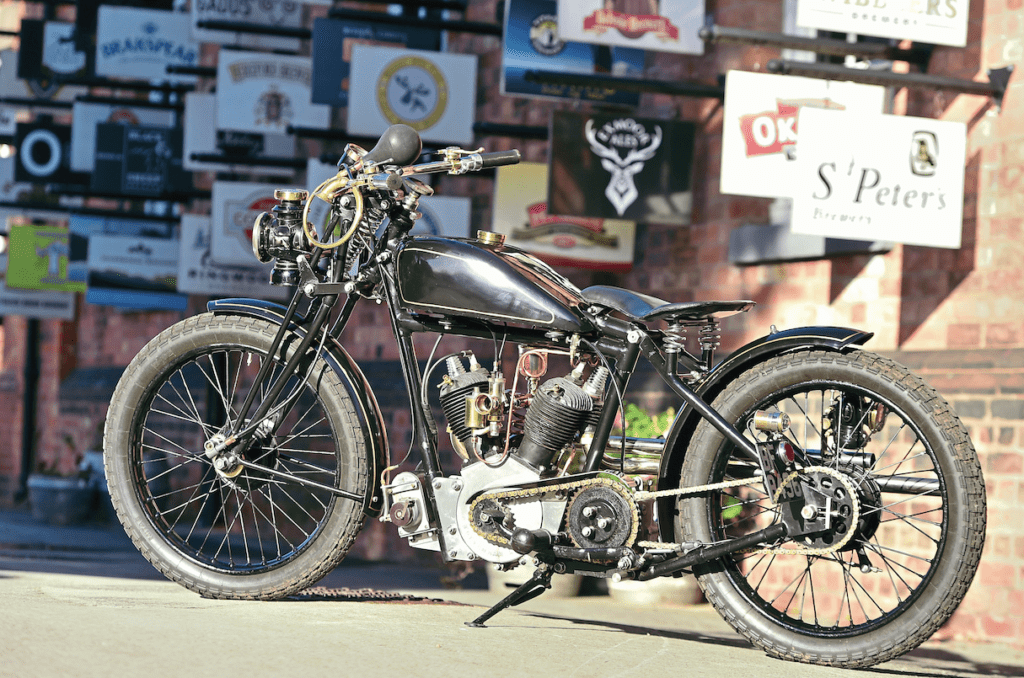

As you’ll know if you saw the last issue of the magazine, a gentleman by the name of Richard Tunstall, whose absolutely beautiful one-off hybrid BSA/Harley-Davidson single was in it, also has another restored, and of course modified, bike too; this one here in fact.

This particular motorcycle started life as, and still is really, a Coventry-Eagle; a bike so rare these days that most of us, if we’ve ever actually seen one, will’ve only ever seen it in a museum somewhere.

Enjoy more Back Street Heros reading in the monthly magazine.

Click here to subscribe & save.

I say ‘most’ because many, many years ago, back in the very early Nineties, I actually happened upon one parked on the side of the road in a small village on the old A11 a few miles south of Cambridge.

Somewhere among the old photos that I haven’t looked at in an eternity there’s a dark and possibly quite out-of-focus picture of it; I had no idea what it was, other than a very old British bike of some sort, but it was unusual enough for me to remember it to this day, and I can honestly say I never, ever thought I’d ever see a custom one.

Coventry-Eagle was a British bicycle and motorcycle manufacturer who started making bicycles in Victorian times under the name of Hotchkiss, Mayo & Meek. The company name changed to Coventry-Eagle in 1897 when John Meek left, and by 1898 they’d begun to experiment with motorised vehicles. A year later they produced their first motorcycle.

Each was hand-built and proved reliable, and by the First World War they were using Villiers and JAP engines. During the early 1920s, models changed depending on what engines were available, and the company swapped between five engine manufacturers; Villiers, JAP, Sturmey-Archer, Blackburne, and Matchless.

Their Flying 8 was probably the most iconic bike of its time, and bore a resemblance to the legendary Brough Superior. During the depression of the 1930s, they concentrated on producing two-strokes, and production continued until the start of the Second World War in 1939. After the war, they were too small a company to continue competitively making motorcycles, so they concentrated on the racing bicycles they made under the name of Falcon Cycles.

The remains of the bike you see here were rescued from a scrapyard in Rhodesia some 50 years ago by a guy who always planned to restore it, but found that it was far beyond his capabilities. About three years ago, having done nothing much with it for 47 years due to its advanced stage of damage, he decided to sell it, and Richard bought it for a price so low you just wouldn’t credit.

That was probably a blessing really as the 680cc JAP engine’d been severely damaged; the crankcases’d been smashed hard against the flywheels, and the pistons seized solid in the barrels, and there was, pretty much, nothing else left of it. Using all his draughtsman and tool-making skills (he’s classically trained in both disciplines) he spent several weeks just removing the pistons, then rebored and lined the barrels, fitting pistons from a BSA A7SS.

He repaired the cases, and then set about making new big end bearings, new main bearings, new cams (cam blanks were first turned, then profiled used a hacksaw and files, constantly checked with a degree plate and clocks, and finally case-hardened and polished), new cam followers, new valve guides, and a whole host of other bits needed too.

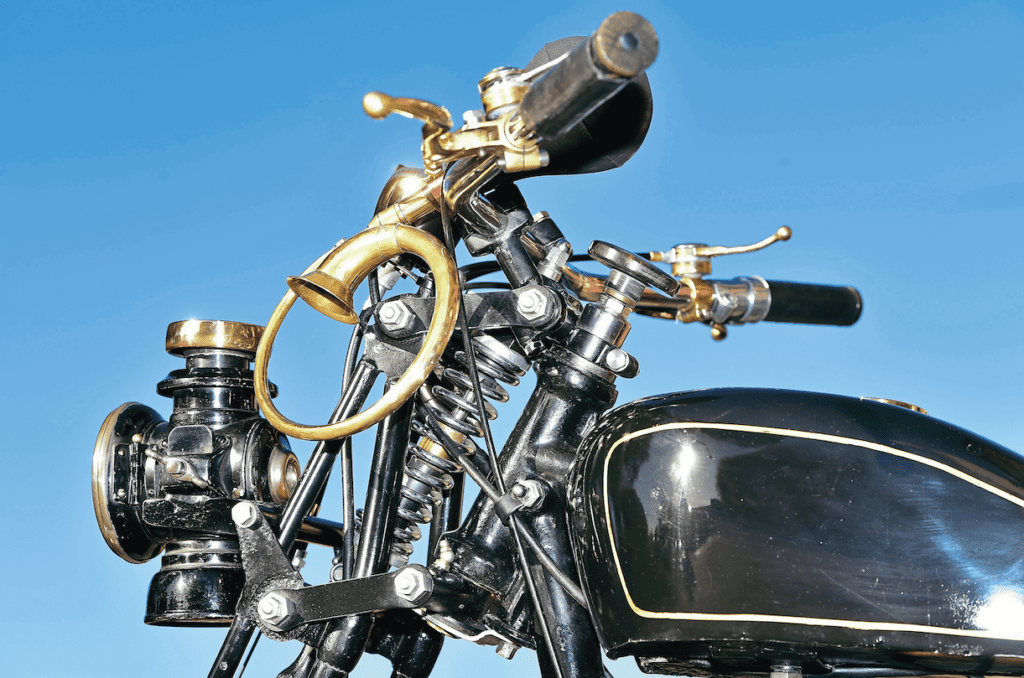

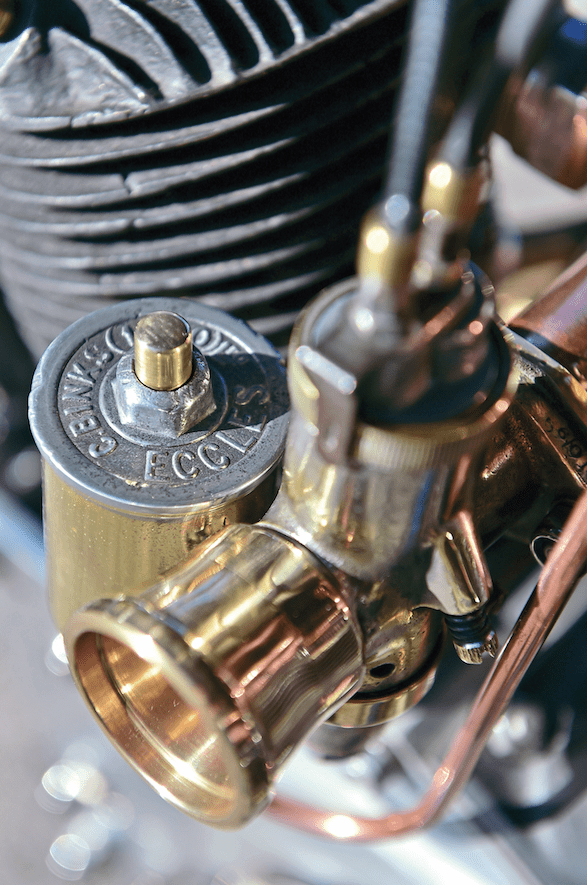

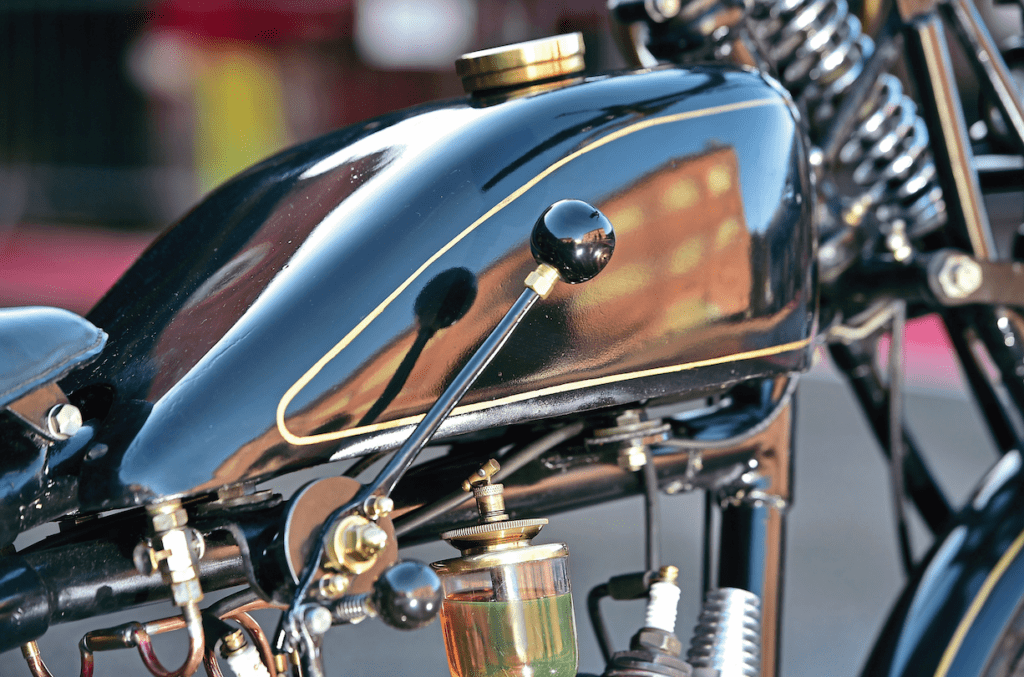

He fitted an Albion clutch and gearbox, linked to the engine by a chain-driven primary, and a chain-drive magneto was sourced from a Morgan museum. Everything else is his own work too; everything from the Amal carb with its remote reservoir to the copper oil and fuel lines to the one-off stainless ‘pipes, and just to get the engine alone to this state took six months of hard work.

Once that was done he set about repairing and/or collecting all the parts he’d need to have something he could put the engine into. As you can probably imagine, parts for Coventry-Eagles aren’t the easiest things to find, and so when he did find something it required a lot of work to get it back to usable.

The frame, reputed to be a 1930 item, needed extensive remedial surgery, as did the girder forks, the wheels, and the drum brakes, and the list of parts he made for it (including that amazing speedo drive) as they were unobtainable is far too lengthy to list here.

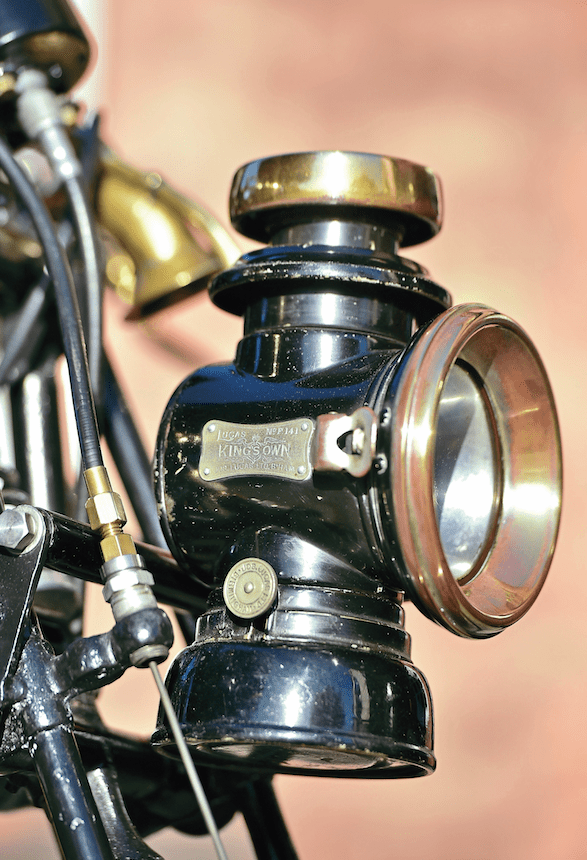

As with the single last issue, he did all the work himself, including converting the vintage paraffin lamp into a headlight, putting LEDs into the old rear light, wiring the bike, painting it, and doing all the finishing himself too.

He spent a fair amount of time setting up the engine, and the rest of the bike too, and now it runs as sweetly as a well set-up JAP should. It’s not a bike he uses that often, he admits, but then it is in excess of 80 years old, and he has the single and a scrambler in his stable too. When it does come out though, it performs flawlessly, and rides like a bike half (okay, three-quarters…) its age. It’s also, as you can see, quite, quite gorgeous…

Thanks to the folk at the National Brewery Centre in Burton-on-Trent for allowing Richard and Simon to do these pics on their site. If you have any interest in beer (sorry, I know that was a dumb thing to say) and brewing, then it’s worth a visit – ring them on 01283 532880 or go to www.nationalbrewerycentre.co.uk to arrange a look-see.